By Brian MacKenzie

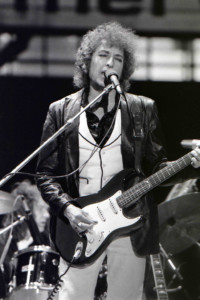

Earlier this month, Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for the poetry tucked into his song lyrics. After weeks of silence — no issued statements or acknowledgment of the award, save for a brief mention on his website that was removed — Dylan mentioned to a reporter from The Telegraph that yes, he’ll be at the Nobel Prize ceremony, “if it’s possible.”

While only speaking from our own experience and without judgment or interpretation, Dylan’s silence long silence and reticent acceptance flies in the face of society’s current fascination with play for approval. And we identify with you, Mr. Dylan.

Seeking acceptance for doing what we love is different from pursuing our passions for the sake of satisfying that fire that burns within. For some, the achievement of races and competitions is crossing the finish line. There’s an identity inherent in finishing a marathon or an Ironman. For others, the achievement was set in motion just by signing up for that race, by committing to learn from the training process. It doesn’t matter your goal – what matters is your understanding of your own reasons why and learning from that process.

As Endurance athletes and coaches, when we look at what we’ve done with the Endurance training movement in general, our sports have never been perceived as sports of position. Running especially has been something athletes just do. Suffering included.

But there’s a learning process to training, not only of your body but of yourself. In anything we do, from sitting down to picking something up, to moving across a horizontal plane to climbing over something, we make innate shapes. We see people making shapes as they move, transforming in and out; speed and distance limited only by our fitness, our mobility and by the strength of our minds. Everything plays a role in how we move. When range of motion is limited, when we try to force something that isn’t there, we experience pain. But when we allow ourselves to move properly, to feel that pain and be present with it, everything connects. We are nothing more than a reflection of our openness and our willingness to learn from everything. Everything is connected.

But there’s a learning process to training, not only of your body but of yourself. In anything we do, from sitting down to picking something up, to moving across a horizontal plane to climbing over something, we make innate shapes. We see people making shapes as they move, transforming in and out; speed and distance limited only by our fitness, our mobility and by the strength of our minds. Everything plays a role in how we move. When range of motion is limited, when we try to force something that isn’t there, we experience pain. But when we allow ourselves to move properly, to feel that pain and be present with it, everything connects. We are nothing more than a reflection of our openness and our willingness to learn from everything. Everything is connected.

As Endurance athletes we fixate on the clock. Our mile times, our race PRs. But running a four-minute or five-minute mile is not a complete definition of your fitness. Technique and strength, mobility and flexibility sit astride your reasons for wanting to run a mile that fast. And when ego takes a front seat, the entire goal is headed on a collision course.

The all-mighty lion. © Derek Ramsey. Used with permission.

In the end it all comes down to the behaviors and thoughts that mold who we become. Our posture is reflective of our physical and emotional strength. You don’t see the strong and powerful lion with weak posture. Healthy animals have healthy posture and healthy movement. We are no different. There’s an inherent freedom in understanding yourself and why you’re doing what you’re doing. Learn from yourself at the deepest levels.

So back to our friend and Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan, whose radical personality has always flown counter to mainstream culture. While we can only speculate, his long silence before acknowledging the praise of an audience may have been a deep gut check on his passion, his talent, his motivation, his reasons for the why in everything he does. Or not. No matter what Dylan’s reasons, his introspection reminds all of us to pause and discover something that may be difficult to consider: that there’s no real difference between Dylan’s perceived hesitation and our need to run a 100-mile race. It doesn’t mean we can’t go out and do it – but it’s a deep gut check on the reasoning behind it.